Du’a

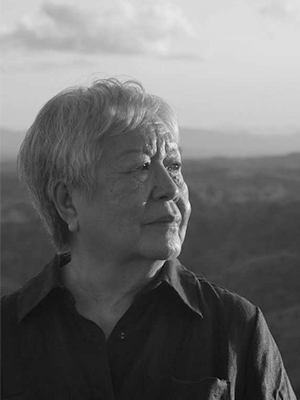

For Ramon Pagayon Santos

after listening to Du’a

Here words are of no use.

Sound signifying without fury.

Only ancient branches shaking, grass leaves

rubbing against wind. Stand at the edge

of the jungle or by a stream where water

washes over stone. Listen. Alive among the leaves

or under the rocks digging into the loam

or swinging among the vines crawling

under the brush the flourishing multitudes

they know their kind without words

without names to call them by—knowledge

borne by scent color shape gesture—or sound

twittered screamed whispered sighed across

the vast secrecy of trees—the love call death song

prayer laughter anger grief of myriad lives

No words. Only infinitude of sound held

in the pulse of blood diverse arrhythmic

beat breath fingers flexing feet stamping dancing

on the wounded earth. Stand on a street in the

midst of any city among these seven-thousand islands

where your name is not spoken nor any word answer

to your speech. Here people can hear the hunger

in your voice they could read the fear in your glinting

eyes they know whether you come in peace or war, though

no words are uttered. They would trade roses for

your stories they would dip into the aged wine jar and

drink with you cup after cup, spilling the ripened fragrance

of their dreams their memories as you smile to tell them

you have crossed to their mountains with a clean heart.

You may hear the violins crying the voices of women

praying for rain for harvest for peace mourning lost sons

the malong ripped from young bodies of their daughters

grain spilled and wasted on the sand that will feed no child,

the cold hearths in abandoned villages. No need of words.

Just listen.

I gather these poor words for you, Ramon Santos,

to tell you what I heard in your music. I heard

the Archipelago talking--the sea the islands mountains

multitudes thriving, each in their own homes, each

speaking the strange tongue of its kind but yet

answering to one another with the sound clarity of need

in perfect understanding

without words.

A Day in the Life of Rowena Guanzon

She stood in front of the Manila Cathedral, flanked by two nuns.

The spectacle had attracted a little crowd, a few reporters.

A row of microphones to send her voice from this tiny piece of ground

in the vast metropolis, to the vaster air lanes, northward to Batanes,

all the way to the southern outposts of Tawi-tawi.

2:00 p.m., Manila time. Was it noontime in New York?

Breakfast time in Australia. Tea time in London, wine

in Rome or Barcelona, coffee everywhere else, it did not matter.

It was her time to speak.

She spoke in English, understood across all geographies of the world,

even in Ilocandia, where they grow tobacco on the stingy land.

Where a Marcos had sprung, dead these thirty-three years now,

but whose unabsolved ghost, rasps like a dull saw in the national memory.

Insatiable, his living spawns would swallow whole mountains if they could.

They holding us still in the grip of perpetual hunger and need, dangling

a myth of gold before our gullible sight. Poverty drives us to unreason

and that is how we are caged. Standing in front of God’s own edifice,

she might have wanted to pull us back to truth, telling us about

the lies, the deceptions, bribery and corruption, how

your human rights and mine are trafficked for their greed.

Do you think we listened? Did we understand?

Women sweating under the sun selling hot chilis, okra

and string beans by the roadsides, did they hear her words?

Housewives pinching pennies for a meager measure of rice,

a string of salt fish, did they listen?

And what about the men and boys in warehouses and building sites,

cement dust caking on their sweaty skin, hunger like rats’ teeth

gnawing at their insides, could they have heard her too?

Did her voice echo across the canefields of Sagay, Bais, Kabangkalan,

the fish markets of Bantayan, the Taboan in Cebu, rife with the smell

of dangit, ginamos hipon, buwad bolinao, ever the poor man’s fare?

Did her words reach the eerie mountainsides, the villages in Mindanao,

tribesfolk mourning their dead sons and daughters, their villages

perished in fire, their memories pillaged by dishonor

and the anger of dispossession?

When she had had her say and fell silent,

who would remember her speech?

Only a poet whom everybody knows,

is mad, not worth a thought.