Dinner Parties

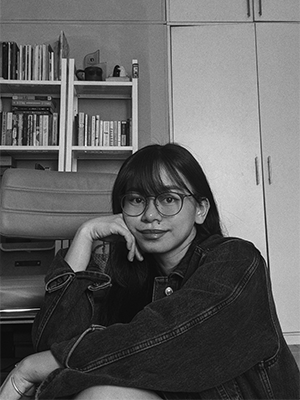

Lakan Umali

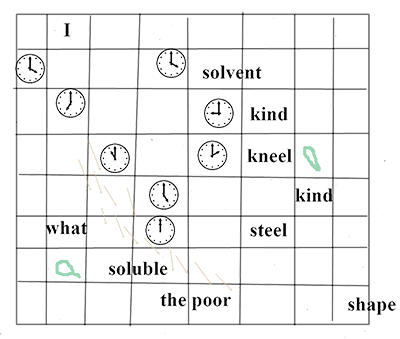

What makes a good dinner party? Lights, laundered table-cloths, prime cuts of pork, valet parking, light music, a dynasty or two, indentured waiters in uniforms, top-shelf alcohol, melons and other palate cleansers, a trade treaty or two, greens, some foreign loving, deals leading to dominion over those outside the dinner party.

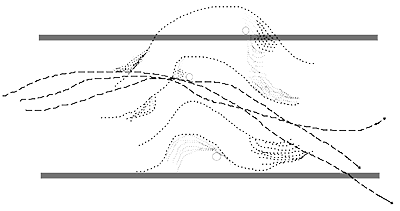

I often turn down invitations to dinner parties because of a lack of garments, companions, transportation, or energy. I think of the hours people spend at work. A person regularly rots for nine hours at their office or station. Commuting eats four hours from their daily schedule, two if they’re lucky, but let us stick to four because luck is a garnish found only among dinner parties and other activities of the bourgeoisie. Assuming the person ekes out seven hours of sleep a night, that leaves four hours a day for dinner parties, cooking and other chores, worship, consumption of cultural junk, dissociation, family bonding, ennui, character development, and other non-quantifiables.

I am tempted to include dinners parties in the same category as nuts and shrimps: nuisance allergies. I find myself growing increasingly weary of decadence. This weariness is not borne out of a Marxist hatred for class. In fact, the classes at dinner parties are usually very beautiful; fine laces and silks on bodies scrubbed clean by papaya soap and cow fat, teeth white enough for Schengen visas, plump cheeks, nourished faces, no ingrown bones here. Instead, I find myself averse to the decadence, as when a child gorges herself on too many sweets and throws up on her parents’ bedsheets. I find it strange that I have grown weary of something I rarely experience, and yet I am weary of it just the same. Perhaps it is the nature of capital: to present one with so many lived, decadent lives that one soon imbibes them all as their own, and retches at the thought of imbibing more.

Perhaps one of the most famous parties in Philippine politics is not the Liberal Party or the Nacionalista Party, but a party thrown by the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. On his yacht gathered dozens and dozens of the country’s most shimmering and straight-toothed beasts. In the grainy footage from CBS news, one can see a grown man in a baby's bonnet and diapers burst out from a cake and scream, Mama, Mama! His nipples are visible beneath the pink frills of the bonnet. Elsewhere in the video, Marcos' son, Bongbong, croons his own version of USA for Africa's, We Are the World. The sweaty, loquacious little liar is now overlord to 115,600,000 Filipinos. “There are people dying/It's time to give a hand to life,” he sings, voice shorn of harmony or conscience. I do not know if it is too much to ask for a president too poor to own a yacht.

I prefer sleep to dinner parties. I find my bed much more comfortable. It is not really a bed in how beds are advertised and formed in the collective consciousness; it is more of a piece of stretched-out fabric with a lot of stuffing. My bed’s legs have long ago collapsed, so the bed is firm on the floor. But the ground is solid, sturdy. And there is more space for me now that you are gone. But a bed is still a bed. And a dinner party is still a dinner party, even when it does not have the requisite chandeliers, hors d’oeuvres, waiters, intelligentsia, gun runners, social climbers, kalachuchi centerpieces, and food. Even when the dinner party is a bucket of gin bulag and a wobbly table, it is still a dinner party, because it is important for referents to always refer to something, otherwise language loses meaning. Perhaps if the dinner party were the latter and not the former, I would be less reluctant to refuse. I prefer dinner parties where less is given and less is expected.

Another reason I dislike dinner parties is because the most fastidious of them are held in places of high security. I cannot stand the sight of guards or barbed wire ringing the walls of the subdivision surrounding the manse. I do not like bag inspections, inquiries about my last visit to Davao, CCTV cameras, and the various ways capital polices my person. To be honest, I do not know why I am still invited to these particular dinner parties. Perhaps blood is thicker than water. Perhaps the host imagines I will write a story, poem, or article about the party when it is over, extol the hospitality of his family, the fizziness of his champagne, the soft hands of his new wife. Perhaps I am a sanitizing agent.

In the Soviet Union, Imelda Marcos dines with Prime Minister Aleksei Kosygin. She leaves flowers at the memorial of the first man in space. In New York, free of draconian dinner parties of Moscow, Imelda Marcos engorges herself. $193,320 worth of antiques. A $6,240 Sheraton writing desk. An $11,600 George II wooden table with a marble top. What are the limits of capital? Certainly not $330,000, which Imelda Marcos spends on a ruby-emerald-diamond necklace, and not $1,150,000, which she sacrifices to a platinum bracelet. At dinner parties, she sings and dances for American politicians, Republicans and Democrats alike. Even they are surprised at her opulence.

Many year later, I sweep the floor. I wipe the table, cook the rice, boil and season the vegetables, light a candle to keep mosquitoes away. I set a place for you. I call your phone but you do not answer. My love, where are you? Is your mind as sharp and bawdy as I remember? I hope you are with like-minded loved ones. I hope you are eating fresh bananas and mung bean soup. I hope the forest loves you as a son. You imagine a better world is possible. One day, we will dine together.

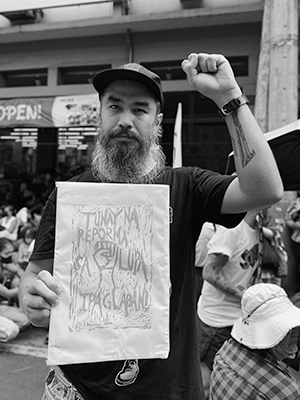

Acceptance leads to degrees of complicity. Glitter and good food renders complicity palatable, but complicity is still complicity. Acceptance leads to some short-term gains, and the fulfillment of immediate needs absolves the venial sin of complicity. But who bestows absolution? And who yearns for it? And how long can the lull of acceptance muffle the explosions, the sour rumble of bellies, the silence of another blackout, the cries of children in the infernal afternoon? Capital does have its limits, if one squints hard enough, dreams green enough, chants in regular and upward motions, strikes at the soft wormy heart of greed. All dinner parties end eventually. And some guests are more complicit than others.

I often turn down invitations to dinner parties because revolutionaries are elsewhere. I know where to find you.